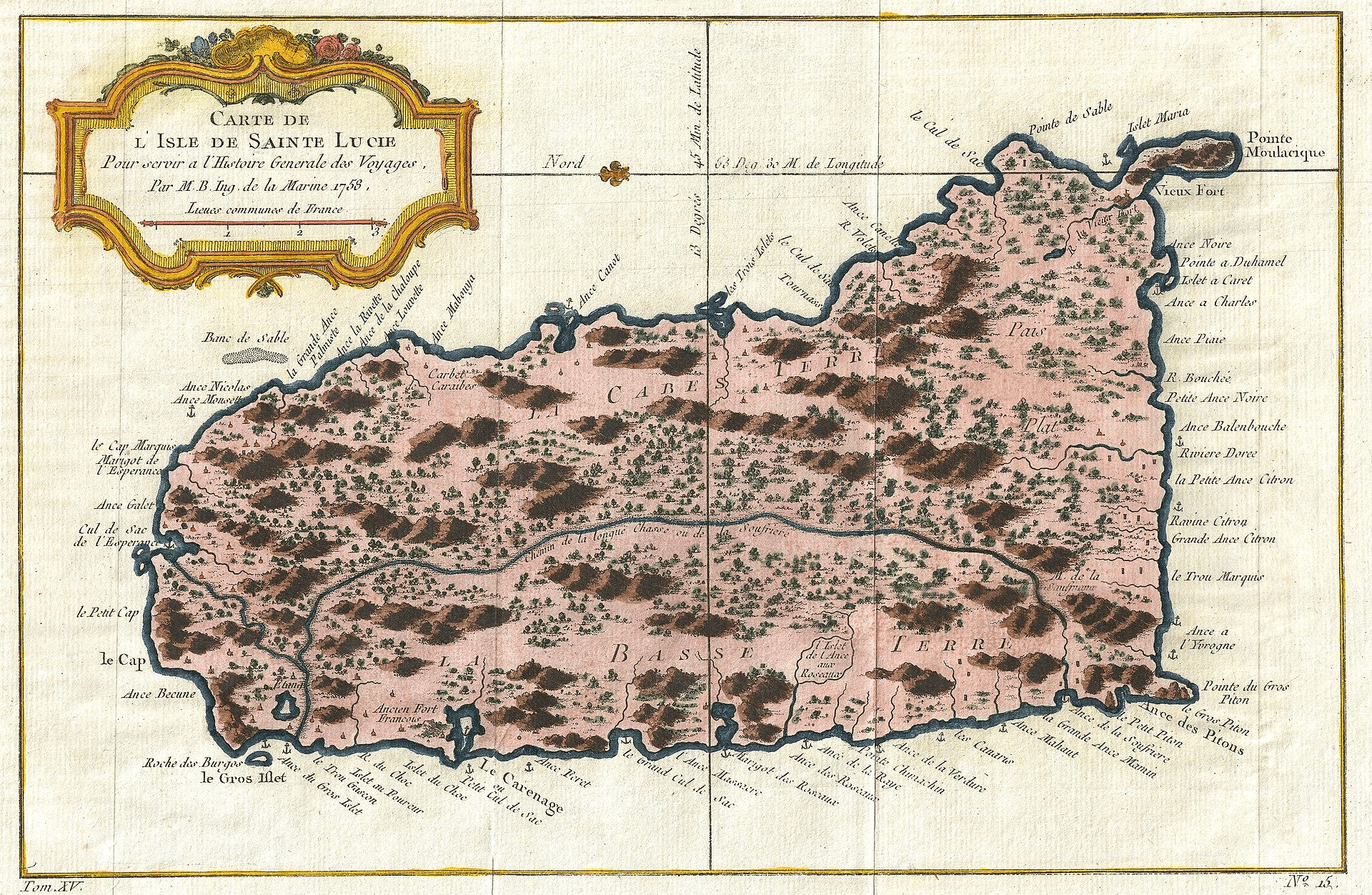

Saint Lucia traded hands in the 1760s and 1770s, first being occupied by Britain in 1762 during the Seven Years’ Wars before being given back to France as a part of the agreement made in the Treaty of Paris on February 10, 1763. Nonetheless, it fell into British hands again in 1778 following the Grand Battle of Cul de Sac, which took place amid the American Revolution. After this settlement, the island’s population saw a considerable increase. In the year 1779, there were 19,230 inhabitants composed of 16,003 slaves who toiled on 44 plantations throughout the island. The estates shuffled in much profit for the British. However, the settlement did experience setbacks such as the Great Hurricane of 1780, which took the lives of around 800 enslaved Africans.[1]

The French proved a formidable force, and following the 1783 Peace of Paris, they restored their rule of Saint Lucia in 1784. British slaveowners deserted three hundred plantations, and thousands of slaves marooned and settled the interior of the island as a result of the power shift. The French Revolution also sparked a surge through the island as the national Assembly dispatched four Commissaries in January 1791 to spread the revolution philosophy. Consequently, slaves began to desert their estates prompting the Governor of the Island to flee. Revolutionary pamphlets were soon being distributed in 1792 encouraging free Blacks, creoles and poor whites to join patriot forces and arm themselves as they rallied behind the slogan Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité, meaning Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity.

Indeed, the French Revolution’s period proved to be the most tumultuous in the island’s history, especially within Soufriere between 1789-1797. Soufriere became famous as a Revolutionary headquarters and site of one of the most significant battles in St. Lucian history. This was a momentous occasion as St. Lucians of all races and classes joined the French revolutionaries against the British including the enslaved who were omitted in the idea of Liberté, Égalité, or Fraternité. [2]

Disturbances sparked on many plantations, the events of January 1, 1791, especially attest to this and the spirit of the Blacks involved who were pursuing freedom and equality. On the estate of Mount Viet in Soufriere, slaves partnered with maroons and requested their liberty from planters who reported them and invited the militia to quell the uproar. Ultimately, the leaders were captured, tried, and executed. Their severed heads were then placed on spikes and displayed around the parish to douse any other revolutionary forces. However, this move simply agitated the slaves who swore to keep fighting and avenge their fallen freedom seekers.

When France declared war on England and Holland on February 1, 1793, the government installed a new Governor General Nicolas Xavier de Ricard, to secure the island of Saint Lucia. However, the island still fell to the British invasion on April 1, 1794, under a militia led by Vice Admiral John Jervis. They instantly began to transform things and cement their occupation, transforming Morne Fortune to Fort Charlotte. Nonetheless, a patriot resistance who called themselves the L’Armee Française dans les Bois fought back. This declaration began the First Brigand War.[3]

The rebels were said to be led by Flore Bois, an escaped female slave who took solace in the woods and lived amongst maroons after growing tired of physical and sexual abuse at the hands of her owner. The rebels sought to establish a Free Colony in St. Lucia and rid the island of the British. With the Blacks of the Island still disturbed by the 1791 incident, their retribution was delivered in 1795 when Flore deemed them ready for war and received a tip that the British were attacking. Supported by the French Revolutionary Victor Hugues’ arms and troops from Paris, the slaves charged the British and began their revolt. They were joined by six hundred French Republican soldiers who landed on April 18, 1795 and augmented their force of 250 local Republicans and 300 Blacks. The army carried spikes, and some held rifles plundered from the British. They formed formidable ranks attracting more slaves into their march as they went on, and they aided in non-combatant duties.

Flore and her army first unleashed their wrath on Soufriere slave owners in what is known as the Battle of Rabot. They successfully killed several slave owners, brought their plantations down to ash, and freed several slaves who joined their ranks. Moving forward, Flore took it back to the source of her pain and slaughtered her master before burning down the plantation. The marches were not clean sweeps. The British who survived sought solace in another part of the island, the Castries. Regrouping there, the British landed more than a thousand troops at Vieux Fort before marching back to Soufriere to recapture it. The attack occurred on April 22 at Fond Doux and Rabot, and the rebels who the British deemed Brigands proved to have more tactics and prowess. They claimed the victory and held onto Soufriere after they defeated the British on June 19 in the epic battle which had led to seven of eleven towns and villages being decimated aside from Gros Islet, Castries and Soufriere.

With the retreat of their enemies, the remaining Saint Lucians enjoyed what they called a year of freedom from slavery or “L’Année de la Liberté.” A Frenchman Gaspard Goyrand became Governor of Saint Lucia after previously serving as the island’s commissary. Goyrand declared the abolition of slavery and put many aristocratic farmers to trial. Many were beheaded on the guillotine in the act of poetic justice, echoing the events of 1791. Goyrand continued to bring order to the island, which was in disarray by reorganizing it. He appointed Black Commandants in each district to restore production as the rebels destroyed many plantations, and a shortage of food was occurring. Unfortunately, he only served for ten months as the British recaptured the island on May 25 after launching another attack led by Sir Ralph Abercrombie. The French ultimately had to surrender, and General Moore was appointed by the British as the next Governor of Saint Lucia. He encouraged the soldiers who were once slaves to reclaim their roles on the plantations. However, many slipped away into the woods and began a new campaign to regain their freedom. The rebel army, “LAarmée Française dans les Bois” was formed once again. They fought in defense of France, but their most significant incentive was their liberty.[4]

General John Moore fought valiantly against the Brigands but failed to subdue them. James Drummond succeeded him. Drummond was relentless and cruel. By the end of 1797, he had managed to defeat and decimate the resistance. He placed the surviving rebels into their regiment after their surrender and repatriated them to Africa. The Brigand War had scorched the surface of the island, depleting its population and vandalizing its landscape. For the British to enjoy their spoils of war, much work went into establishing order, rebuilding infrastructure, and organizing a colonial administration. [5]

[1] Soufriere Regional Development Foundation, “History of Soufriere,” Soufriere Foundation – St. Lucia, 2010, http://soufrierefoundation.org/about-soufriere/history.

[2] Soufriere Regional Development Foundation, “History of Soufriere.”

[3] Soufriere Regional Development Foundation, “History of Soufriere.”

[4] Soufriere Regional Development Foundation, “History of Soufriere.”

[5] Soufriere Regional Development Foundation, “History of Soufriere.”